Frances Thomson

self and art

Mona Ryder, self and art, is prismatic, offering multi dimensions of viewpoints and readings. It is this complexity that attracts artists and accolades to her door but lands her art in the too difficult basket for mainstream appreciation and interpretation. To her detriment in a commercial art world, Ryder has employed and mastered a spectrum of media: painting, printmaking, sculpture, textiles, text, artist books, jewellery, installation, assemblage, soundscapes, and includes those associated with women’s craft: sewing, stitching, embroidery. She cannot be pinned down or categorised. Her commercial success, or lack of it, along with scant widespread public recognition, is of little interest to her. It is necessary that she values integrity and follows her own impulses and promptings, as Ryder is a contemporary social critic.

Listen, 2016. Connecting Threads, Grace Cossington Smith Gallery, Sydney, 2019. Curators: Lisa Jones and Mary Faith.

Silver Sword, 2016. Connecting Threads. Materials: fabric, embroidery, paint, artificial plants. Photo Credit: Richard Glover.

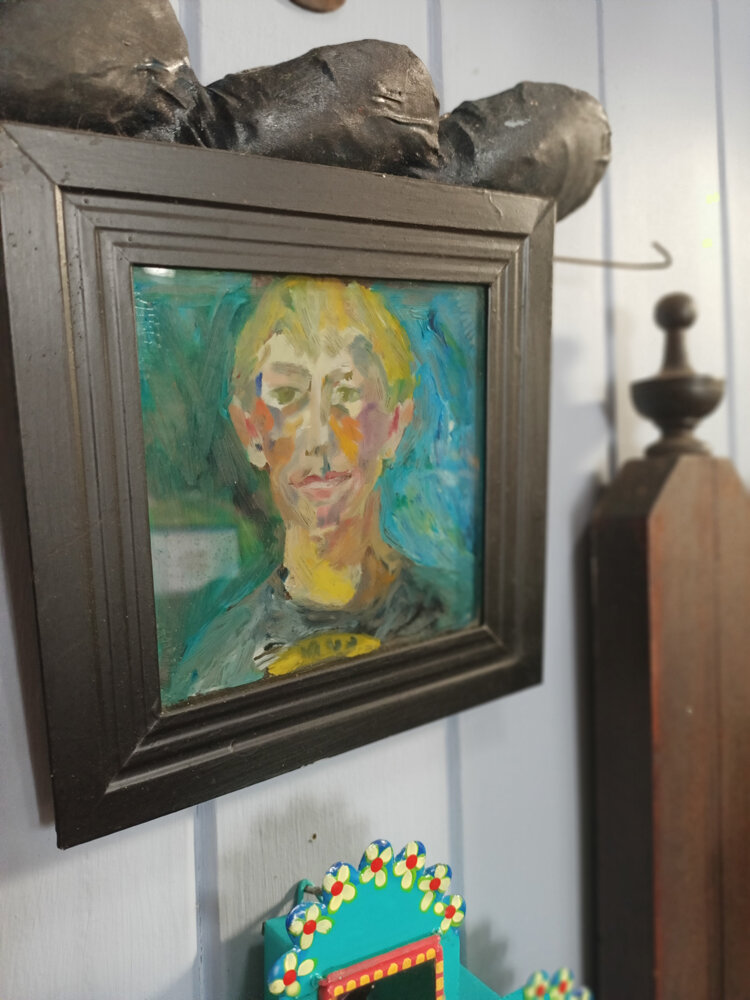

Ryder draws from her own context, contending with and embracing paradox. While her bookshelves are packed with art books and her side tables are laden with the latest topical publications, Ryder mines the concerns of her life. Her living space, a ranging, double storey, multi-roomed, grand Queenslander, with a separate studio, is a showcase for her art, many of her works in states of becoming: dis- and re-assembled over time. Ryder’s relationship with her husband, Paul, one of mutual respect, is as close as it gets to healthy human interaction, and forms the bedrock of her life. In her self-portrait, Loose Tongues, Paul and their dog are ever-present and ever-watchful. Relationships with family and friends are paramount and her generosity to those in her circle is legendary.

Loose Tongues, 2012. Percival Portrait Prize. Perc Tucker Regional Gallery, Townsville.

I am surprised that Mona’s art has not garnered wider appreciation, and over the years I have made efforts to redress this, with varying degrees of success. Writing Mona Ryder is a project proposed by Craig Ball that will morph into a digital footprint of text and images, a welcome impetus for greater acknowledgement of Ryder’s contribution. True to character, Ryder has selected writers oblivious of any strategic alliances that will enable them to further promote her work. From a basis of long term relationships she has chosen those she considers ‘clever’. Intellectual stimulation is a necessity to Ryder and she knows what it means to have an active intellect and to operate outside the dominant power structures. Ryder is vested in process and it is from the process that she will derive her enjoyment and benefit. I suspect that the true beneficiaries of this project will be the writers, the women that Ryder, as matriarch, has encouraged and brought to her table to share in the camaraderie. For Ryder sees part of herself in these younger women and has involved each of them in her project to support and galvanise their own creativity.

All of the writers are women and all are involved in the arts – as artists, curators, teachers, gallerists – and have known Mona for a considerable period; knowing Mona is indivisible from knowing her art. Ryder has previously described herself as a feminist, but as that term becomes more nuanced and difficult to pin point, it would be more accurate to call her a humanist. Her work derives from her own life experience: her intense social bonds, the impact of a year at a girls’ Catholic boarding school, her emotional struggles, subverting gender stereotypes, female archetypes (Ryder exhibited Mother Lover Other at the Queensland Art Gallery in 1995), aging, death and dying, to name some of the concerns traceable in her art.

Works in the family home. Materials: shoe soles, paint, shell beads, bottle opener, holy water container, mussel shells, silk.

Ryder adopts a mode of representation that suits her reality, repurposing domestic items to carry her ideas, transforming and transcending the everyday into social commentary. She has formed a vocabulary of materials, assigning different personal meanings dependent on the context in which they are used.

Mussel shells can reference the vagina, pubis, or a carapace. Ties and tongues proliferate, suggesting genitalia; the anthurium a preferred image as it can signify either male, female or hermaphrodite. Ryder’s invitational work for the 2005 National Sculpture Prize, Les Animaux Sauvage [Wild Animals] that satirises the corporate body, its power, control and conformity, features red silk ties. Stuffed and installed in such a way to heighten their reference to phalluses, the ties bear commercial labels that read ‘Trust Me, Man Made, ‘100% Pure Guile’. The installation included a large three dimensional text of ‘PLOT’ covered in faux fur and wall printed twisted text in the shape of a tie where the word ‘TRUMPED’ immediately grabs our 2021 hyper-awareness. Ryder’s biting yet humorous critique uncannily anticipated the rise of Donald Trump.

Les Animaux Sauvage, 2005. Installation View, Sculpture Prize. National Gallery Of Australia, Canberra. Materials: stuffed silk ties, fake fur, text and sound. Photo Credit: Victoria Garnons-Wiliams

Ryder persistently chooses to work with the colour red, hand dyeing textiles blood red, a colour that has myriad associations: love, menstruation, open wounds, anger, sexual allure. She explores our familiarity with chairs, reconfiguring recycled chairs that are capable of giving or being removed from support, the palimpsest of previous users hinting at the fragility and transience of a life. A crutch, usually not paired, is an obvious support to a damaged human that in Ryder’s hand alludes to the crutches we all need to navigate our being in the world. Dance Me to the End of Night, an installation at Murray Art Museum in Albury in 2016, assembled many of her recurring materials. Suspending momentarily the impetus to find meaning, the installation worked aesthetically, a symphony of predominantly black and red, tactile and static. A central installation of floor to ceiling hanging black rubber tubes suggests movement, as do the paired shoes surrounding them. A chandelier of mussel shells threaded together with red leather, shields and spears add to the set. Ryder exploits perceptive and cognitive uncertainty and ambiguity – none of which can be fully resolved by the artwork per se, but require the viewer’s immersion in the experience to decode multiple and layered meanings.

Starting with the title, alluding to Leonard Cohen’s Dance me to the end of Love, a suggested interpretation is of aging and memory. The ‘creatures’ in the middle are shuffling, decrepit elderly dancers. They are surrounded by dress-up shoes filled with shells, faux fur, lilies, and hair, poignant memories of their past. All the shoes now fitted with electrical cords either no longer plugged in or ready for plugging in to life support; some have wheels attached for ambulation. The chandelier still elegant but not of crystal, just a shell, the mussel banquet eaten long before, the trail of red dyed stockings at its base harkening back to earlier times, the blood now drained.

Dance Me to the End of Night, 2016. Installation detail. MAMA (Murray Art Museum Albury). Curator: Bianca Acimovic. Materials: Bicycle inner tubes, steel shoes, electrical plugs, mussel shells chandelier, ballroom essence bottles. Photo Credit: Simon Reeve.

As we become more differentiated as individuals, do we aspire for our unique experiences? Mona trials her installations in her current studio, an intimate space not replicated where her exhibitions are held. A private viewing is charming, and the artist relishes her viewers having a familiarity with her art or contemporary practice to provide feedback. Well-versed in art theory – Ryder began but never completed a doctorate on her own work – she aspires for and achieves a level of complexity in her practice that defies reductive readings. A published writer who uses text in her artwork and who carefully considers her titles- many forming multiple entendres- Ryder eschews commentary, adopting a version of ‘let the work speak for itself’, stating: ‘Words often allow an inlet to understanding art, but art expresses feelings and emotions that are fundamentally too complex to verbalise. To explain fully is to say that work need not exist.’

It will never leave me, 2018-2019. Lone Star, Artisan Gallery, Brisbane. Materials: antique frame, glass containers with sand, hair and sea water with casuarina needles, embroidered text. Photo Credit: Don Hildred.

In an act of generosity and respect, Ryder will not commentate or be didactic, allowing viewers to arrive at their own interpretations. The paradox is that in a space where we look for fast meaning, Ryder’s work is an unfashionable slow burn. If you take the time, you are rewarded with wisdom and insight, a space that you have to enter by yourself.

A student and teacher of art, well-versed in art history and familiar with a spectrum of artistic practice, Ryder’s ranging intellect seeks daily engagement with art- be it her own practice, her own collection, attending exhibitions, or reading books or on the internet. Although engaging with any and all art, even those she finds annoying, serve to provoke a response, she is particularly receptive to that on the margins. So called ‘primitive’ art of PNG and Africa, and Indigenous art, attract her and she is particularly drawn to and resonates with the work of women. Frida Kahlo, Mona Hatoum, Georgia O’Keefe, Louise Bourgeois, Rebecca Horn, Annette Messager, are some of those whose work she knows well. Most of these international artists were suggested to her by friends and colleagues who see some similarities in Ryder’s practice.

Red Room, 2018-2019. Installation view detail. Lone Star, Artisan Gallery, Brisbane. Materials: wooden chairs, rose petals, framed work. Photo Credit: Mark Sherwood.

For Ryder it is comforting to see that other artists parallel her work and from whom she can take reassurance and inspiration. The ironies are legion. Ryder’s practice has its parallels internationally, fitting her work on a world stage, while those who have been most receptive to her work have been women and they generally run the regional galleries, where she has shown extensively. Therefore Ryder, whose work can be provocative and discomfiting, exhibits on the margins, while the national and state galleries show a list of predominantly male artists. A major statement by Ai Weiwei is de rigueur for Australian galleries: the Queensland Art Gallery is currently showing Ai Weiwei’s gigantic crystal chandelier, Boomerang, a gift from the artist, in its watermall, a space that was first negotiated for exhibition by Ryder in 1995 (Mother Other Lover).

Mona Ryder has a consistent exhibition history, with works held in major public and private collections, has been a recipient of various awards, grants, and residencies, the most recent in 2014/15 an Australia Council Residency in Rome. Ryder can be counted as a significant Australian artist. While she is greatly regarded and celebrated by the arts community, Ryder is, however, comparatively lesser-known to the wider public. Amongst the reasons for this is her reluctance to promote herself outside of her artistic milieu. Her work as social commentary critiques commodity culture and she is consistent in not making work to sell.

Untitled, from Mona’s Visual Arts Board residency, Australia Council for the Arts. British School, Rome, Italy, 2014.

Only intermittently has she been represented by a commercial gallery, a necessary part of the business of art and from where work enters collections and receives greater exposure. Her choice of material saw her labelled as ‘the ironing board lady’ in a Bulletin article 1987, conflating her identity as an artist with her materials, an expression of perplexity about her choice of material and of reading her work. Certainly, this demeaning moniker contains gender bias and as an artist, Ryder is marginalised within western art. That has certainly been another and continuing reason for her under-developed public profile. In 2019, 71% of arts graduates were women at the same time that state and the national galleries continued to under-represent that gender at 33.98% and 25.48 % respectively. While the wider public remains largely unaware of her practice, Ryder is compelled to make art and in doing so she is a beacon for women artists.

In recognition of her practice, Ryder was given a survey at the Queensland University Art Museum in 1984. With almost another 40 years of artistic production since then, a retrospective, and major exhibition on the international circuit, are well overdue.

Frances Thomson

Born in Scotland.

Transplanted to Australia.

Art has been a primary focus, as an appreciator not a practitioner.

A keen recycler, attempting to make as small a footprint on the earth as possible.

Chooses to live in the North in a sunny state of mind.